Photo by JudySummerPhotos.com

Stiltsville is a story of revelers, rule-benders and escape. This collection of wooden fishing shacks built on pilings in the shallow waters off Cape Florida is found within the watery boundaries of Biscayne National Park. Most likely sprouting up with the advent of Prohibition in 1920, the number of structures through time has increased from a handful to 27, then dropped to today’s seven stilt “homes.” In its nearly 100-year history, threats to the existence of the get-away-from-it-all shacks would come in the form of hurricanes, fires, the law and finally, the federal government.

Biscayne National Monument was formed in the southern part of Biscayne Bay in 1968. In 1980, Biscayne National Park was established, expanding its boundaries to the north, which included Stiltsville. Ownership of the land passed from the state to the federal government. Located south-southeast of Miami, it is the largest marine park in the National Park Service’s system of 410 areas. The park spans 173,000 acres and protects the world’s most extensive coral reef tracts; the east coast’s longest stretch of mangrove forest; the shallow waters of the Bay; the northernmost Florida Keys and the artifacts associated with the region’s 10,000 years of human habitation. Stiltsville is one such record of human activity for which the park is responsible.

Initially, the NPS agreed to abide by the owners’ leases until they expired in July 1999 and then they would permanently remove the buildings. After the destruction caused by Hurricane Andrew in 1992 only seven of the stilt homes remained standing. Others had been completely blown apart or so extensively damaged that they had to be razed. Extensions, legal and political wrangling delayed the park’s acquisition of the buildings for public use. Via a complex course of negotiations, public discourse and the “Save Old Stiltsville” movement, a cooperative agreement was signed between the owners and the NPS, preventing the removal of the buildings. Owners of the buildings became “caretakers” charged with the responsibility of maintaining the structures and, through the issuances of permits, making the structures available for use by the public. In 2003, the non-profit organization, Stiltsville Trust, was established. The Trust’s purpose is for the preservation, oversight and the facilitation of public access to the seven remaining structures.

How It All Began

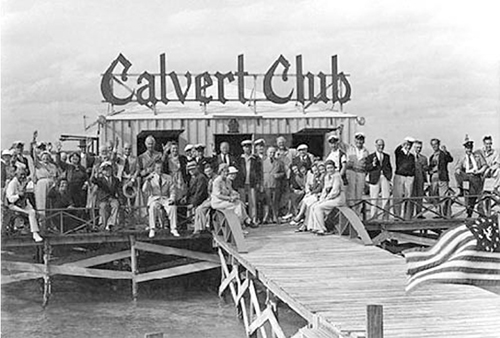

No longer exisiting, the Calvert Club was one of several clubs that flourished on the flats. Another the Quarterdeck Club was the subject of a story in Life and had a big following. The Bikini Club came later

Local historians generally agree that houses began springing up on the Bay’s flats during Prohibition to provide havens for selling or transporting the “demon rum” outlawed by the ratification of the 18th amendment in 1919 (effective January 1920). Seemingly from the beginning, the historic course of the intended use for these “shanties” took two tracks. One was keen to flout the law and the other was to provide, a family-oriented, get-away location in which to enjoy a peaceful day of fishing and swimming.

The first personality of note to stake a claim on the flats was “Crawfish” Eddie (or Charlie) Walker in the 1930s. He opened a bait and beer shop to earn some money from the countless sports fishers flocking to the bay. Eddie made a crawfish chowder he called chilau from locally caught crawfish. Often friends would go out to visit Eddie and enjoy a bowl of stew. In 1937, two city officials and an automobile dealer joined Eddie, constructing shacks of their own built on barges anchored to the shoals. By 1945, 12 stilt houses and two clubs (the Calvert Club and the Quarterdeck Club) dotted the bay’s horizon.

Places to Party Down

State Beverage Agents present objections to Bikini Club proprietor. The raid in progress as “Pierre” is read the complaint. And Pierre’s immediate reaction: “Mind if I have a beer?”

The Quarterdeck Club was built for sportsmen by Commodore Edward Turner in about 1939. Clearly no shanty, the building measured 140 by 80 feet, and had its own electricity, heating, and refrigeration. Members were treated to a bar, dining room, bridge deck, gaming room and an ample wharf for their boats and yachts. The Quarterdeck became quite fashionable, and it was rumored that gambling was helping to support the operation. After World War II, gambling was no longer a rumor but a fact that was tolerated by local law enforcement. Hurricanes, charges of lewdness and more gambling, and finally a fire in 1961 brought the Quarterdeck to an end.

By 1960 the Stiltsville community had grown to 27 homes, but in September of that year Hurricane Donna would blast through and destroy all but seven structures.

Never quite free of the party-going allure, Stiltsville got a new neighbor in 1962. Harry “Pierre” Churchville opened the Biscayne Bay Bikini Club on a yacht grounded on the flats. For only one dollar, one could purchase membership and enjoy nude sun bathing, alcohol and staterooms for private assignations. “Pierre” subsequently purchased a surplus Navy PT boat and ran it aground next to the yacht thereby increasing the size of his establishment. By 1964 the club had 1,300 members, but in1965 the club was raided and closed.

One infamous event was captured by the Miami Herald in 1965. The State Beverage agents raided Pierre’s club. After Pierre finished reading the complaint, he said to the agents,

“Mind if I have a beer?”

Change of Focus

The Miami Springs Boat Club was built by firefighters and police officers

Likely, the community of family-oriented Stiltsville home owners was pleased to see the closing of the Bikini Club.

Dade County Circuit Court Judge Frank Knuck and his wife Esther’s shack was the subject of a Miami Herald feature in August 1965 written by Beverley Wilson:

“The house has its own generator for electric equipment, bottled gas stove and refrigeration, and emergency bottled gas light. Mrs. Knuck catches rain water in a barrel for washing. Out-house style plumbing is ingenious.”

Hoping to promote a better image for Stiltsville, Judge Knuck said, “We’re a family-type colony, not a scruffy bunch of squatters. There’s too much sensational talk about antics at the nearby Bikini Club.”

In early September 1965 Hurricane Betsy changed the look of Stiltsville again, packing 120 mph winds and an eleven-foot storm surge. In the aftermath, the government response this time was different. The county’s Building and Zoning Department required mandatory compliance with its building codes by the owners of the homes in the watery community. The shacks had to stand up to 120 mph winds and be at least 10 feet above the water at high tide. Also at this time the

state declared that leases on the flats could not include buildings intended for commercial use, thus ending the threat of more Bikini Club style debauchery in the increasingly family-centric community.

Stiltsville Today

© Photo by Paul Marcellini

The fortunes of the stilt homes on the flats rose and fell with the elements and powerful hurricanes. After Hurricane Andrew in 1992, the final count of structurally sound buildings would be seven. Today, the A-frame house, Hicks House, Baldwin-Sessions House, Bay Chateau, Jimmy Ellenburg House, LeShaw House, and Miami Springs Power Boat Club House still hover over the beautiful waters of Biscayne Bay.

Stiltsville houses have been the setting for novels, magazines, movies and television. Some have distinctive architecture: the Baldwin-Sessions house with its pattern of receding and protruding elements (designed by architect and caretaker, Gail Baldwin); the A-frame house strengthened with telephone poles; and the LeShaw house’s mansard roof. Fundraising events for charitable, education, communal and service organizations have taken place at many of the homes over the years. Judges, elected officials, social clubs, Broadway and sports stars have enjoyed the view of Miami from the flats. The Miami Springs Power Boat Club (established in the 1950s) hosts many charities and raises funds for the Boy Scouts and the Optimist Clubs.

When working to save Stiltsville Antoinette Baldwin received many letters of support for the project; some wrote, “I just want to know they are still there.”

Planning a Visit

© Photo by Paul Marcellini

First, if you are friends with one of the caretakers and you are spending a day out there with them that, works very well.

If not, know that the houses are available to the public however there is a procedure in place that must be scrupulously followed. Warning: do not tie your boat up to a Stiltsville home, piling or dock if you haven’t first gotten legal permission. Your action is considered by the caretakers and the Park Service to be “trespassing” crime.

Special visitation permission can be gotten by contacting the Stiltsville Trust. Depending on the nature of your request, you may require a special use permit from the NPS in addition to permission from the Trust. And if you aren’t an experienced boater, pay strict attention to the fact that you must rely on the navigational aids if you don’t want to run aground.

Historian Arva Moore Parks shared ownership of a Stiltsville home, later destroyed by Hurricane Andrew. In recounting her experiences on the flats she said,” A wonderful place to raise a family; my kids still have very fond memories. It was a great way to grow up.”

NPS:

Stiltsville Trust:

- At the Dade Heritage Trust Stiltsville Exhibit (2016). Stiltsville house owner and architect Gail Baldwin, discusses the features of the house with visitors.

- Sara Goldsmith, 6, and brother Bryan Goldsmith, 9 fish on a dock in Stiltsville. Published April 24, 1988.

- Bikini Club at Stiltsville. Published July 25, 1965.

- The Miami Springs Boat Club was built by firefighters and police officers

- Stiltsville Trust Knight Arts Challenge – Via The Miami Foundation