Writers for the Works Progress Administration observed in Florida Negro, a Federal Writers’ Project (ca. 1935),

“With one or two notable exceptions, the Florida Negro lives in Negro sections. These sections have one point in common; they are for the most part separated from other sections of the city by the railroad tracks running through the community. This is especially true on the east coast, of which it has been truthfully said that Florida East Coast Railroad is the dividing line of the races. From Saint Augustine to Miami, Negroes live west of the tracks.”

“The ‘Hunting Grounds’ of Cutler were still the haunt of deer, bear, and panther. Indian Creek was a desolate lagoon, haunt of the wild duck and crocodile.

“The Miami River was a mangrove bordered stream, with four or five small buildings on its whole length. There was no Coral Gables, no Miami Beach, no race track, no golf course, not a single orange or grapefruit grove, nor even the suggestion of a truck farm. There was not a mile of road anywhere, the water of the Bay being the only highway.”

1917 Looking east on Sunset from the train station.Marshall Williamson (1890-1972) is among the early settlers who came to south Florida at a time when the farming and lumber industries were expanding to larger markets thanks to the growth of the railroads. Williamson left his native city of Madison in north Florida, an agricultural and industrial area which became the County seat, to settle in the relatively new and sparsely populated town of Larkins (later the City of South Miami) in 1912. Named for Tennessean Wilson Alexander Larkins (1860-1946) who settled in an area near current day Cocoplum Circle in about 1897, the town was established in 1899.

Eventually, Mr. Larkins owned scores of acres of farmland, operated a small dairy, the post office, a general store, and with the coming of the rail line to what is now Sunset Drive and Dixie Highway, a commissary, packing house, and siding with station where the tracks crossed Larkins Road (Sunset Drive). Along with other growers and lumbermen, Larkins purchased land closer to the FEC railway as the center of the small settlement shifted westerly. The railroad and those who came to south Florida as tourists, laborers, and service men on their way to the Spanish American War (1898), helped to fund the businessmen and homesteaders who created what officially became the City of South Miami in 1927.

Dorn Brothers Packing House on the west side of the rail (1917).Farming and entrepreneurial families settled or established businesses in and around the Town of Larkins: Dowling, Dorn, Opsahl and Galloway, among others. Brothers, Harold and Robert Dorn from Chicago settled in the Miami area about 1910. Harold Dorn wrote, “We had started to ship avocados and mangoes ourselves in 1913, and in 1914, we built a packing house [Dorn Fruit and Vegetable Company] on the Larkins side-track of the Florida East Coast Railway for all local produce, vegetables as well as fruit.”

Unlike the White pioneers who came to the area, Mr. Williamson was unable to own or live on land east of the FEC railway. As an African American he was prohibited by the South’s “Jim Crow” laws passed in the late 19th century as a way to legalize racial segregation. The US Supreme Court’s decision in 1896 (Plessy v. Ferguson), signaled approval of such laws and maintained they were legal as long as they were “separate but equal.” Other laws enacted in the State of Florida strengthened legal segregation throughout the state and remained in effect well into the 1960s prior to passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Second class citizenship permeated every facet of life for African Americans like Mr. Williamson for decades, including where one could build a home, raise a family, worship, and attend school.

Old St. John’s AME ChurchThe City of South Miami was faithful to Jim Crow laws and parcels of land west of the FEC railroad were deemed the appropriate area in which African Americans could reside. In 1928, the city’s Ordinance Number 40, entitled “An Ordinance Providing for the Segregation of the White and Colored Citizens of the City of South Miami, Florida” was enacted dictating where the city’s Black residents could live. One exception was those “Negro” persons living in servant’s quarters while in the employ of Whites on the White employers’ premises. In the 1927 City Directory, listings include the letter ‘c’ in parenthesis to indicate that the resident is “colored.” Common occupations cited are laborer, domestic, chauffer, carpenter, driller, farmer, cook, grocer, and porter.

Marshall Williamson is credited with being the first Black landowner in Larkins. He purchased land spanning from today’s SW 64th to SW 66th Streets and from SW 62nd to SW 65th Avenues on which he built houses.

Black Church membersWilliamson, standing at 5’4” was known affectionately as the “Little Mayor” of the African American community. An astute and generous businessman, he was integral to the community, improving it in countless ways over his lifetime. He donated land on which Saint John A.M.E. Church was built on SW 59th Place in 1916 and for J.R.E. Lee School located on SW 62nd Avenue. The area around the church became known as “Madison Square” after Williamson’s hometown in northern Florida.

Among community members, fond memories of Williamson abound. James Richardson, III speaks of his great uncle Marshall and life in South Miami in the decades spanning the 1920s to the 1950s. His father James Lewis Richardson, II, was raised by his uncle Marshall after the loss of his parents at a young age.

“Before the community had electricity, Uncle Marshall used to go around building little contained fires to light the streets so that neighbors could gather at night to talk and kids could play games.”

Williamson home (current)At one time there were exactly two people who owned telephones in the community. This was in the days of “party lines” as opposed to private lines. Mr. Williamson would allow anyone to use his phone and if word came in about a job or a family emergency, Williamson would take a message and get it to the intended person.

“Uncle Marshall wanted the kids to have something to do and to stay busy. So, during the late 40s, once a week, he set up a movie and showed it outside, using the wall of one of his houses as a screen. We saw movies and serials and we had popcorn and lots of fun,” said Richardson.

Williamson’s kindness was directed at children and adults alike.

“People went to him for advice, both personal and political. He was probably the most helpful person in the community,” said Richardson. “Although he did have to keep people out of his mangoes! But if they asked for some, he’d give ‘em to them.”

Mango orchard next to Williamson home.When it came to city hall, his grand-nephew reported that “His word meant something downtown. I think he had good relationships with downtown.”

The “Little Mayor” was an activist and an advocate for the rights of African Americans in South Miami, encouraging Blacks to vote and helping to solve community issues at mediation meetings held in his home. The first church services for St. John congregants were held in his home, also.

Said long-time resident Daisy Harrell of Williamson, “I remember him as this wonderful man who was always out walking and talking in the community.”

Mr. Williamson’s residence is located at 6500 SW 60th Avenue. Built in 1935, the home is typical of residential construction of the period. Following the Great Depression, housing tended to reflect traditional forms, yet with minimal decoration. The City of South Miami’s historic designation report for the Williamson home describes it as one story, rectangular in plan, featuring a shallow-hipped roof covered with asphalt shingles. A carport occupies the northernmost one-third of the structure, emphasizing the increasingly popular role that automobiles were playing in the daily lives of Americans. Later in the history of the home a veneer of synthetic stone was installed on the building’s exterior.

The Williamson home was designated a historic site within the City of South Miami on April 18, 2006 for its association with a historically significant person from the city’s past and for its architectural integrity.

Marshall Williamson was honored by the city, first by proclaiming “Marshall Williamson Day” on September 17, 1969 and in 1975, naming a park for him. The proclamation, issued by Mayor Jack Block and the City Commission states, “Upon this occasion of a testimonial to honor Marshall Williamson, it is both fitting and proper that the citizens of South Miami recall and remember the man known for his civic pride in our community …

Photo Credit: GR0788, State Library and Archives of Florida.

John Robert Edward Lee, Sr.

John Robert Edward Lee, Sr.

Marshall Williamson donated the property on which the J.R.E. Lee School stands. John Robert Edward Lee, Sr. (1864-1944) was born into slavery in Seguin, Texas. An early leader in the cause of African American education and a lifelong educator, he served as the third president of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), a historically Black college from 1924 to 1944. Under his administration the university gained in academic status. By 1944, there were 48 new buildings, an accumulation of 396

more acres of land, and a marked

increase in the number of students

and faculty.

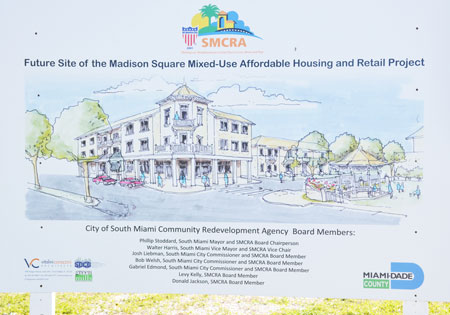

MADISON SQUARE

MADISON SQUARE

PUBLISHER’S COMMENTARY

Among other civic, educational and religious concerns he addressed, Marshall Williamson was a champion for housing and economic viability in his community.

And the Madison Square community thrived.

However over the course of some thirty plus years, the housing inventory within the “Williamson Historic C ommunity,” (a/k/a the CRA), has been seriously depleted to the tune of some 160 units gone. Often multi-family housing was replaced by single family homes or lots vacant for years. Local businesses housed in and servicing the community, all owned and operated by African-Americans have all been torn down and gone, with the exception of one.

Enter the Madison Square project. You would think a project that addresses the chronic need for affordable housing and provide opportunities for business would be on a fast track in improving the lives of many.

Yes, you would think. Madison Square, a mixed-use development project, would invariably be the catalyst for sustainable economic growth in the community.

For many years visions were conceived, community charrettes held and plans discussed. Since 1994, there are no fewer than five Madison Square studies. And yet nothing.

If the community appreciates the designation as the “Williamson Historic Community” and “Madison Square” then in the spirit and wisdom of the “Little Mayor of South Miami,” the community ought to come together as one and work with the city officials and planners to get it done.

It’s about time, don’t you think!

– jes