On June 25, 1927, W. A. Forster was sworn in as South Miami’s first Mayor, and the City began its eight decade journey. In this second part of our six-part series we note some of the early political issues, and recall the olfactory and economic stimulation of the Holsum Bakery and its impact on this new city into the 1950s.

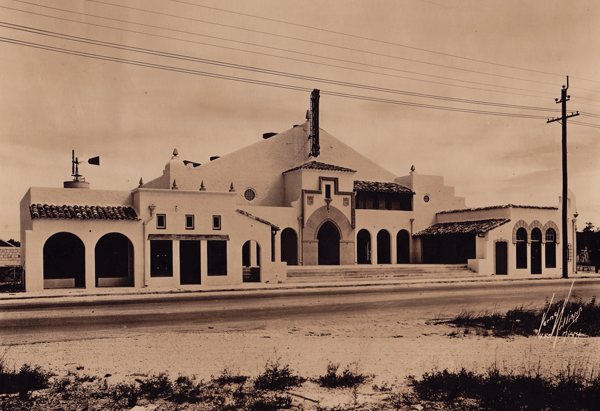

Holsum Bakery fabled water tower at Red Road & Sunset Drive

Early Throes of Political Woes…

Early Throes of Political Woes…

The youthful city of South Miami, according to city historian and mayor, Paul U. Tevis (History of the City of South Miami), struggled to govern itself in the early decades of its existence: “Friction between factions began to show itself; discontent with the Council was manifested by the numerous heated debates or arguments that occurred at Council meetings…” Tevis goes on to say that these debates sometimes ended with irate citizens and Council members resorting to “fisticuffs.” With the mayor as the chief executive officer and the council members as department heads, there were frequent resignations and many instances of strong disagreements between the mayor and police chief. The movement away from a mayor-centric form of government resulted in the voter-approved referendum to change the charter to a city manager form of government, enacted in 1953.

The fire truck that saved the city.

One of South Miami government’s early purchases (and source of indebtedness) was a fire truck at the cost of $4,150. This humble truck later became the reason the City remained a city. The discord running through the daily management of the city and the resignations grew to such a point that a movement to abolish the municipal government gained enough traction to result in a special election. The election, held June 16, 1931, abolished the City Charter by a count of 184 to 163. The City of South Miami did not operate as a municipality from August 21, 1931 to April 2, 1932.

However, via a Writ of Mandamus issued by Circuit Judge Worth W. Trammell on May 17, 1932, the mayor and council were ordered to resume governing the city as before. The judge cited the outstanding debts incurred by the city as the reason to compel the elected officials to continue operating the city. The chief debt among those cited by the judge was the fire truck. Yet, even this was not quite enough to quell the discontent, and in June of that same year, another (unsuccessful) attempt was made to surrender the Charter.

- The Riviera Theatre

- Shelley Building on Sunset Drive

- 1926 Hurricane Destruction

Business Growth & Devastating Hurricane

Governance issues aside, South Miami saw some major construction projects with such buildings as the bank, Dorn-Martin Drug Company (now the Amster properties), Shelley building, and the Riviera Theater (located at 5700 South Dixie Highway). This building boomlet was followed by the devastating hurricane of September 1926. A record-breaking storm that ravaged much of the region’s new construction and contributed to the bust of the City of Miami’s unprecedented growth (about $60 million dollars in building projects in 1925).

City Hall, situated on the east side of US 1 housed administrative office, the municipal court, police and fire stations (photo 1933). Groundbreaking in 1935 for the new City Hall on the west side of US 1 and its present location.

Baking and Making Dough in South Miami

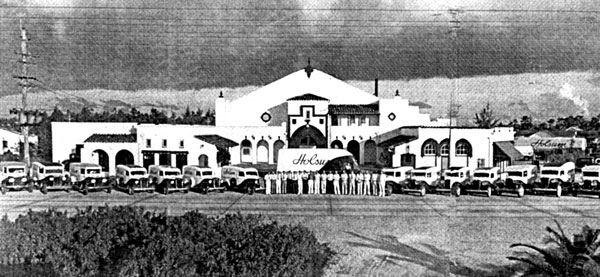

In 1934, the Fuchs Baking Company moved north from Homestead to South Miami in order to be closer to distribution markets. The bakery (later named “Holsum”) was a fixture on the city’s landscape for over four decades with its landmark water tower and warm, comforting aroma of freshly-baked bread wafting throughout the city. Charles T. Fuchs, Jr. moved his business to the old Riviera Theater on US 1. According to the Miami News (1938), “The bakers of Holsum took over that super-super theater and set to convert it into something more practical, a super-super bakery.” The bakery was a very successful business, and Holsum bread became, as the News reports, “The most popular bakery product in South Florida.” The Holsum Bakery grew in the state of Florida and even shipped bread to Puerto Rico, Cuba and Latin American countries.

Charles T. Fuchs, Jr. established a business that was one of the city’s main employers. He was deeply involved with the City of South Miami and one of the charter members of the South Miami Chamber of Commerce, serving as its president for a number of years until 1954, when he died as a result of an airboat accident. Blue Waters Park was re-named in honor of Mr. Fuchs in 1956.

The Riviera Theater was rendered in a lovely Moorish-style, typical of many theaters of the period. It appears that the building’s life as a fancy theater was short-lived, followed by an attempt to make it a nightclub. That, too, failed. The role the theater played as the Holsum Bakery complex was its most profitable and memorable. A lot just east of the complex was converted into a park-like setting and was splendidly decorated each Christmas. After Holsum left the area in the mid-1980s, the old bakery was razed and replaced by the Bakery Centre, which closed in the late 1990s, to be replaced near decade’s end by The Shops at Sunset Place.

The City of South Miami struggled through the decades of the thirties, with financial hardships shared by the rest of the nation. In 1935 an ordinance was passed that set aside land for the purpose of constructing a community center. The project received financial assistance from the Federal government’s Federal Emergency Relief Agency (FERA), later termed the WPA (Works Progress Administration) to design and erect the building, which would be located at 6130 Sunset Drive.

The Sylva Martin Building

The Sylva Martin Community Center is a one-story masonry structure built in a rectangular plan inspired by the simple bungalow. It is dressed in high-quality stonework fashioned from local oolitic limestone. Inside there was an auditorium, stage, dressing rooms, a complete kitchen and sanitation facilities; the original fireplace still graces the building’s interior.

Opened soon after construction, the facility was later dedicated to long-time City Clerk Sylva Martin (1896 – 1988) in 1979. Through the years the building played an important role in the civic and social life of the area. At various times the center served as a meeting place for clubs and fraternal organizations, a hurricane shelter, polling place, public library and USO-style entertainment center, and community center. Today it houses City administrative offices.

The First City Clerk, Sylva Martin

Sylva (Graenicher) Martin joined her parents in South Miami in 1917 at the age of 21. About the early town of Larkins, Mrs. Martin told a Miami Herald reporter in 1986, “After 79th Avenue and Sunset, there were just bullfrogs and tomatoes.”

Sylva Martin

Sylva Martin’s parents, Sigmund (a Milwaukee surgeon) and Louise Graenicher, came to Larkins in 1916, clearing land for their home on a ten-acre site near Sunset Drive and Ludlam. Period photographs chronicle a South Miami with tall pines and scrub as far as the eye can see; and at the Graenicher home, flocks of chickens.

In 1936, Mrs. Martin became South Miami’s first woman city clerk and served in that capacity for more than 20 years, as well as tax assessor, tax collector and clerk of the municipal court.

The Crossroads Building was named an historic building by the City of South Miami commission.

Post-WWII

Like much of the nation, the years immediately following the end of World War II began renewed prosperity for the City of South Miami. A surge in building permits came as a result of the Federal government’s end of the ban on the use of steel and other materials dedicated to military production and the establishment of the GI Bill, which made home ownership, among other benefits, affordable for returning veterans. Many of those non-natives who trained in the Miami area during wartime returned to build their lives in South Florida. South Miami’s growth as a suburban area could be measured in the number of tidy homes being built east and west of US 1.

Groundbreaking for the new City Hall on the west side of US 1 and its present location.

Another sign of the changing times was the construction of the Crossroads Building in the city’s downtown. Conceptualized during a time of exuberance for the “atomic age” and modernity, the Crossroads Building reflected the nation’s belief in a brighter future. The City of South Miami envisioned the same era of prosperity and began to promote itself as “The Crossroads—Where Town and Country Meet.”

Publisher’s Perspective: From Cultural Division to Cultural Diversity

1941: Mayor Frederick Grass (standing right) swearing in the council. (L-R) City Clerk Sylva Martin, Harley Vanderboegh, T. J. Faust, Joseph Gladden, W. W. Brown, John Boshwick.

While in today’s jargon, we speak of “cultural diversity,” such was not the case in times past. It was “cultural division” with definite dividing lines: actual, physical, economic and social boundaries.

Like other “southern” towns, when “Miami” was pronounced “Miamma”, South Miami similarly experienced racial segregation (Ord. 48) and disparities since its incorporation in 1927, and through the subsequent four decades of its history. (One experience we didn’t suffer with, fortunately, were the “race riots” of the late1960s and 1980 – South Miami had a tranquil passing of these events.

In the 1940s the population of South Miami was 2, 600 with blacks representing some 50%. With Ordinance #181, in 1941, the city banned the KKK. In 1949, Officer Finch became the first African-American in the SMPD. Yet, it was only in 1968, the first black was elected to the City Council. He was Leroy “Spike” Gibson, a former police officer and Harlem Globetrotter. Ten years later he was followed by Mr. Jim Bowman, and then others. In 1996-98, blacks enjoyed a majority on the City Commission; and in 1997, Dr Anna Price was elected as the first black mayor. In the mid-1990s, the City has initiated a CRA (Community Redevelopment Agency) and built a community center. South Miami Hospital opened a Pediatric Clinic in the community, to better serve the community.

- Hon. Rev. Anna Price

- Hon. Julio Robiana Jr.

In the 1960s, with the influx of Cubans into the County, the Latin-speaking population of South Miami increased. In 1998, Julio Robaina was elected as the first Hispanic mayor. He later served as a state representative: subsequently failing a bid to return as Mayor in 2012. And as years pass, diversity becomes a better pattern for the “city of pleasant living”

-jes